It is a popular belief that Filipinos are resourceful, a trait the current population takes pride in. But what many call resourcefulness may simply be an effort to survive, to endure until circumstances change. This is reflected in the techniques of arnis, an enduring Philippine martial art.

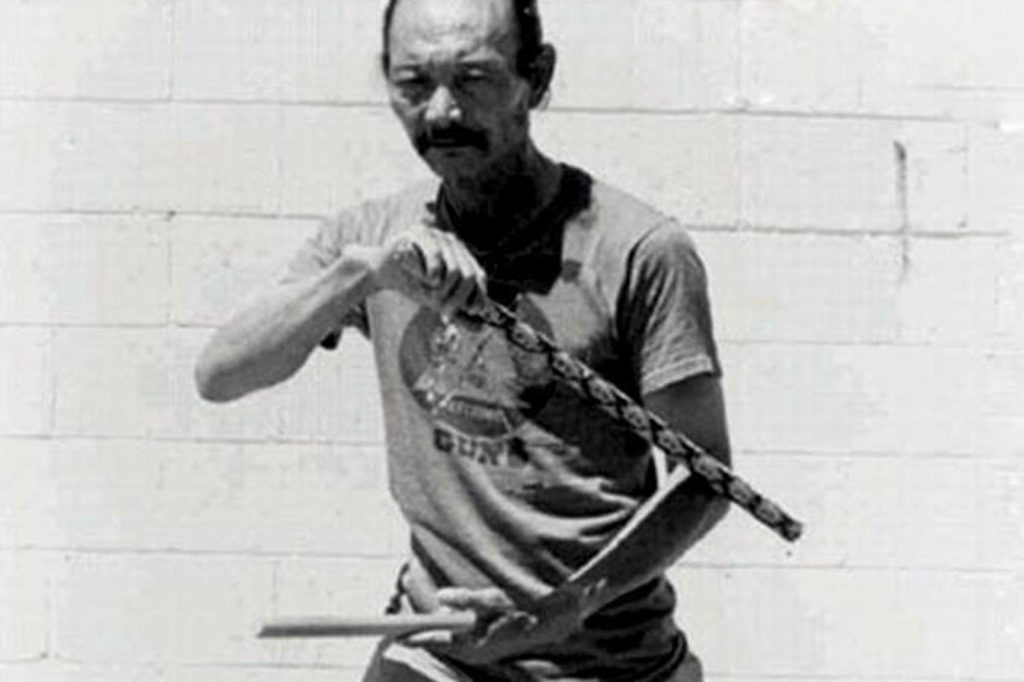

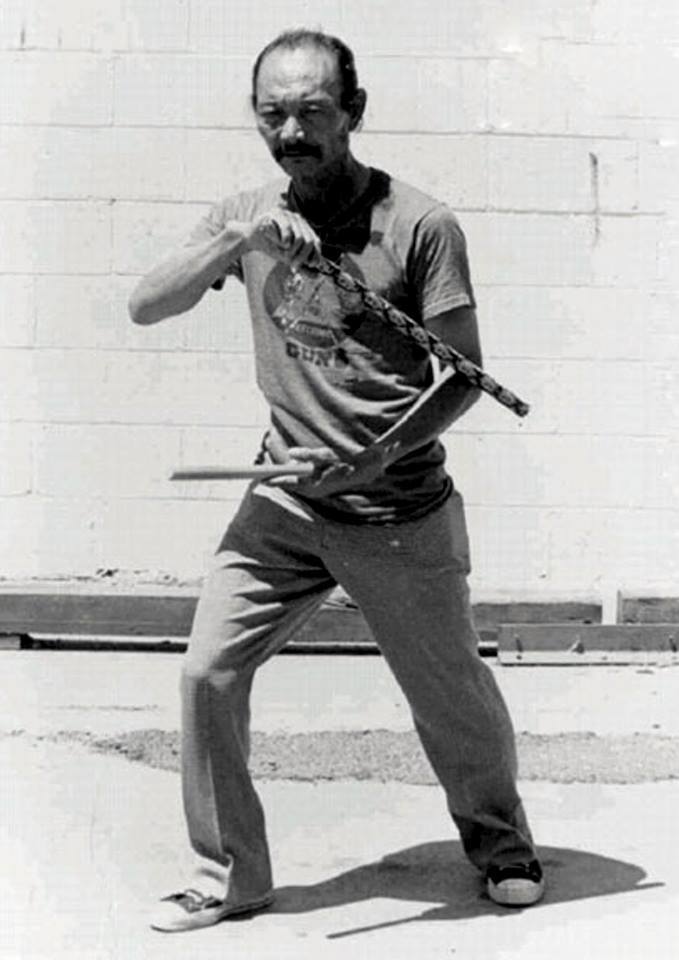

Arnis is a martial art with various techniques. The most popular technique currently, is that of the double sticks (doble baston). But there are also forms of arnis which teach single-stick techniques (solo baston); stick and knife (espada y daga); and knife techniques (daga). Many styles also include empty-hand combat training after a practitioner has displayed sufficient proficiency in their chosen weapon. The empty-hand training includes techniques on choking, throwing, locking, striking, and kicking. The techniques are not flashy but are designed to neutralize the enemy immediately. Arnis has no fancy flips, or complicated progressions either. Additionally, the techniques can easily be executed with improvised weapons.

Its many styles are obvious given its many names. Arnis, the martial art itself, has been called various names: kali, escrima, and baston. And there are more localized names in many provinces of the Philippines. To name a few, the Bisaya and Illongo call arnis, kaliradam; and the Pangasinan call it kalirongan. With such diversity of tradition for one martial art system, it is no surprise that many have attempted to uncover its origins.

Arnis, the martial art itself, has been called various names: kali, escrima, and baston.

Discovering the origins of arnis might just be one of the more frustrating fields of study regarding Philippine culture and history. This is because a majority of pre-colonial Pilipinos did not chronicle their lives and traditions in the pen-and-ink. The ancient Filipinos were people of oral traditions, and of stone and wood carvings. That is not to say that they were not literate, for there is a plethora of pre-Hispanic writing systems, but they were not as meticulous as their European contemporaries in recording their culture through written means.

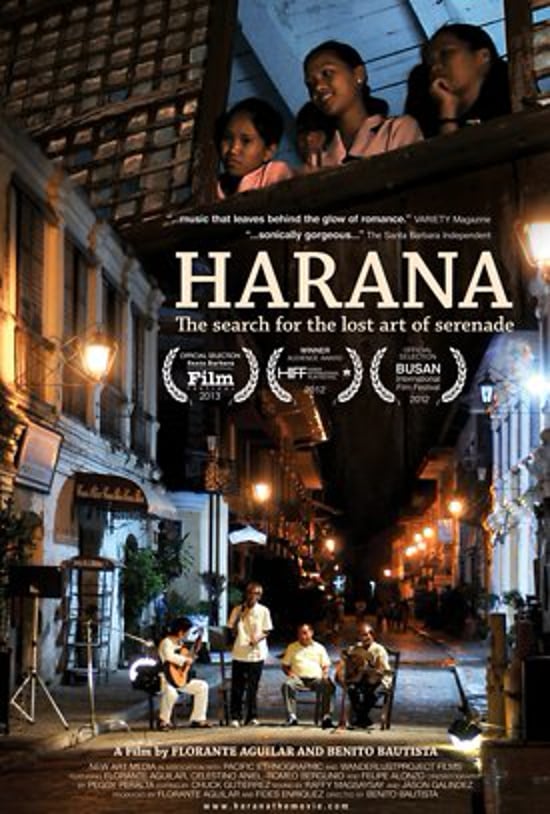

And so, when the Spanish swept through the archipelago, converting the natives and corralling them into towns to fashion them into God-fearing Christians, a great deal of indigenous culture disappeared. This shortened the age of verifiable information. And today, researchers dedicate their lives to searching for the origins of certain traditions and cultural artifacts. Arnis is no exception.

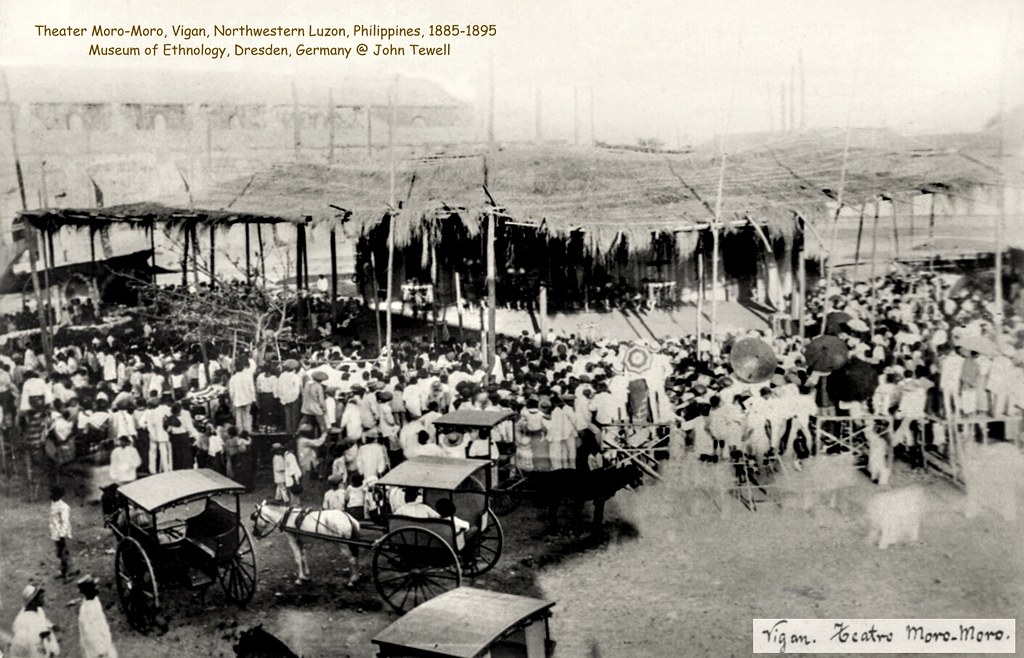

When the Spanish friars introduced the komedya, and the moro-moro, the arnisadores brought their martial art in the form of mock battles. Likewise, folkdances such as the sakuting were utilized as convenient loopholes. The Spanish did not know it, but they had given Filipinos a means of disguising the instruction and practice of the very thing they banned.

Some claim that arnis originated from another martial arts system called tjakalele or silat, from Indonesia. Others believe that it was brought to the Philippines from the Southeast Asian mainland during the Majapahit and Shri-Visayan empires. Still, perhaps more patriotic researchers insist that the art form came into its own in the Philippines, without outside influence. Those that subscribe to the latter also state that any and all similarities with other forms from other cultures must be a product of similar climate, weapons, cultural contact, and a liberal sprinkling of coincidence. Still, others turn to folklore or oral history for stories that might allude to the arrival of the techniques to the islands.

Accounts from chroniclers such as Pigafetta, and from early Spanish friars, recorded the diversity of weapons, warfare methods, and techniques—many of which can be seen in arnis today.

Yet despite this myriad of theories, it is unlikely that a single key event will be found as the origin of the art of arnis. It is likewise highly unlikely that everyone would agree on that one origin without great debate, so perhaps the multitude of possible origins is preferable.

Regardless of where it came from or how far back the practice of it began, by the time the Spanish came around, the many variations of arnis were well established on the islands. Accounts from chroniclers such as Pigafetta, and from early Spanish friars, recorded the diversity of weapons, warfare methods, and techniques—many of which can be seen in arnis today.

These accounts also contain reflections of their writers on how alien these warfare methods and fighting styles were to the conquistadores. The indigenous Filipinos did not wear chain mail; nor did they arrange themselves into infantry and cavalry; and cannons were mostly for maritime warfare. Indigenous Filipinos did not engage in battles in formal battlefields or in the flatlands that are clear of trees. And the Filipinos did not always wait for one big battle, but staged raids and ambushes, utilizing the thick jungle landscape and environment to conceal themselves. In short, the pre-colonial Filipinos did not fight in any way the Spaniards understood.

While no one would immediately think of it, arnis also had its place in the conflicts of World War II. The invasion of the Philippines by the Japanese Imperial Army prompted tens of thousands of ordinary Filipinos into action. Though many enlisted in the Philippine Army, many more ordinary citizens took up arms to defend themselves and drive away the invaders.

Combining the unique manner in which the pre-colonial Filipinos fought with how they did not take to colonialism proved problematic for the Spanish government. Even as late as the 1700’s, when many of the lowlands of Central Luzon and most of the Visayan islands had been occupied for near on two hundred years, Filipinos still occasionally rose in pocket rebellions. The Spaniards feared these revolts, for the unruly Filipino fighting style once again reared its head.

Things came to a head in 1764, when the colonial government banned the practice of any and all martial arts. Likewise banned was the carrying of weapons if one was not a Spaniard or government official. It is not an unreasonable conjecture, then, to surmise that the Spaniards were attempting to eradicate the tradition of arnis not only in practice, but in the minds—the very memory—of the Filipinos. Their efforts, of course, were in vain.

While deprived of their preferred weapons, the arnis practitioners (also called arnisadores) simply refitted their techniques on weapons available to them. Filipinos could still carry riding or whipping sticks when they drove livestock or rode horses. In town centers, it was the fashion for young men to walk around with canes or walking sticks. These became new weapons. The bolo and hand knife, while considered weapons, were also tools and so they slipped through the ban and found their way into the arnis arsenal.

When the Spanish friars introduced the komedya, and the moro-moro, the arnisadores brought their martial art in the form of mock battles. Likewise, folkdances such as the sakuting were utilized as convenient loopholes. The Spanish did not know it, but they had given Filipinos a means of disguising the instruction and practice of the very thing they banned.

The 20th century marked the beginning of the formation of martial arts clubs dedicated to teaching and learning arnis. The earliest written accounts describing organized arnis training dates to August of 1920, when the Labangon Fencing club included not only European fencing, but the espada y daga technique of arnis. This was only the first of many such training clubs.

While no one would immediately think of it, arnis also had its place in the conflicts of World War II. The invasion of the Philippines by the Japanese Imperial Army prompted tens of thousands of ordinary Filipinos into action. Though many enlisted in the Philippine Army, many more ordinary citizens took up arms to defend themselves and drive away the invaders. Several accounts describe the utilization of arnis in close-quarter jungle skirmishes. The war spread arnis exponentially throughout the population because arnis is characterized by simple techniques that were easily applied in actual life-or-death combat.

The end of the war also marked the beginning of an influx of Western influence, and arnis was eclipsed by other martial art forms that grew in popularity such as judo, karate, and kickboxing. Still, martial arts clubs were established, and arnis found its way into them.

In an unfortunate repetition of history, Ferdinand Marcos—who had declared martial law on September 21, 1972—banned the carrying of blades much as the Spaniards centuries ago had banned weapons. Yet, as in the 1700’s, during Martial Law arnis survived solely on a technicality: arnis used the yantok (rattan sticks).

It should be noted that due to this East (domestic)-West (foreign) dichotomy, as well as socio-economic stratification and privilege, arnis became known as the martial art form of the lower classes, or of the provincial country bumpkin.

Still, the 1970s saw the revival and indeed, the golden age of arnis in the Philippines. The secretary of education, Alejandro Roces, helped sponsor the Arnis Revival Movement. This was a movement headed by the Samahan ng Arnis sa Pilipinas (Arnis Association in the Philippines). Included in the efforts were exhibitions at different venues and even on national television.

More martial arts schools opened across the country, especially in Manila. It was not in the tradition of arnis to teach in dojo-like conditions where the advancement of a student rests solely on the master. In fact, certification of titles such as ‘master’ or even ‘grandmaster’ were unusual for arnis until recent times.

In an unfortunate repetition of history, Ferdinand Marcos—who had declared martial law on September 21, 1972—banned the carrying of blades much as the Spaniards centuries ago had banned weapons. Yet, as in the 1700’s, during Martial Law arnis survived solely on a technicality: arnis used the yantok (rattan sticks).

In modern times, arnis has continued to change and evolve as per the needs of its practitioners. One such change is the standardization of a rank and grading system based on years of training and proficiency in technical skills. Certification has also become standard in most martial arts clubs. It is now considered both as a martial art and a sport. Schools have also begun to utilize arnis in Physical Education curriculums, both for fitness, but also to impart self-defense techniques.

One form of the arnis technique that was formerly used in the komedya and moro-moro has survived to become exhibition or theatrical arnis. In the present day, this branch of arnis has further evolved into the arnis found in cinematic productions. It has found its place in action films, with many fight choreographers employing many arnis techniques, if not the weapons themselves. Arnis is so widely practiced, known, and acknowledged that there have been campaigns for the martial art to be nominated and find its place on the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists.

In the same way, art forms, whether it be pottery-making, weaving, or self-defense and warfare, must evolve if it is to stay alive, pertinent, and useful to its people.

Indeed, arnis reflects the Filipino people. Through history, despite dubious origins, arnis has changed and endured, adapted and survived the centuries despite any and all attempts of cultural and identical extinction. Arnis also reflects a quality of “culture” in general: culture survives and persists because it is flexible, adaptable. In the same way, art forms, whether it be pottery-making, weaving, or self-defense and warfare, must evolve if it is to stay alive, pertinent, and useful to its people.

Sources:

Bormann, N. History of Arnis. Connect.gonzaga.edu. Retrieved 21, May 2021

Jocano Jr, F. P. (2001). A Question of Origins. Arnis: History and Development of the Filipino Martial Arts. Boston and Rutland: Tuttle, 3-8.

Paman, J. G. (2007). Arnis self-defense: stick, blade, and empty-hand combat techniques of the Philippines. Blue Snake Books.

Wiley, M. (2012). Arnis: Reflections on the history and development of Filipino martial arts. Tuttle Publishing.

“Sports Arnis Grading System”. https://web.archive.org/web/20170709004436/http://www.arnisphilippines.com/Downloads/RANKS/iARNIS-GRADING_SYSTEM-Public-v02.pdf. Retrieved 21, May 2021.